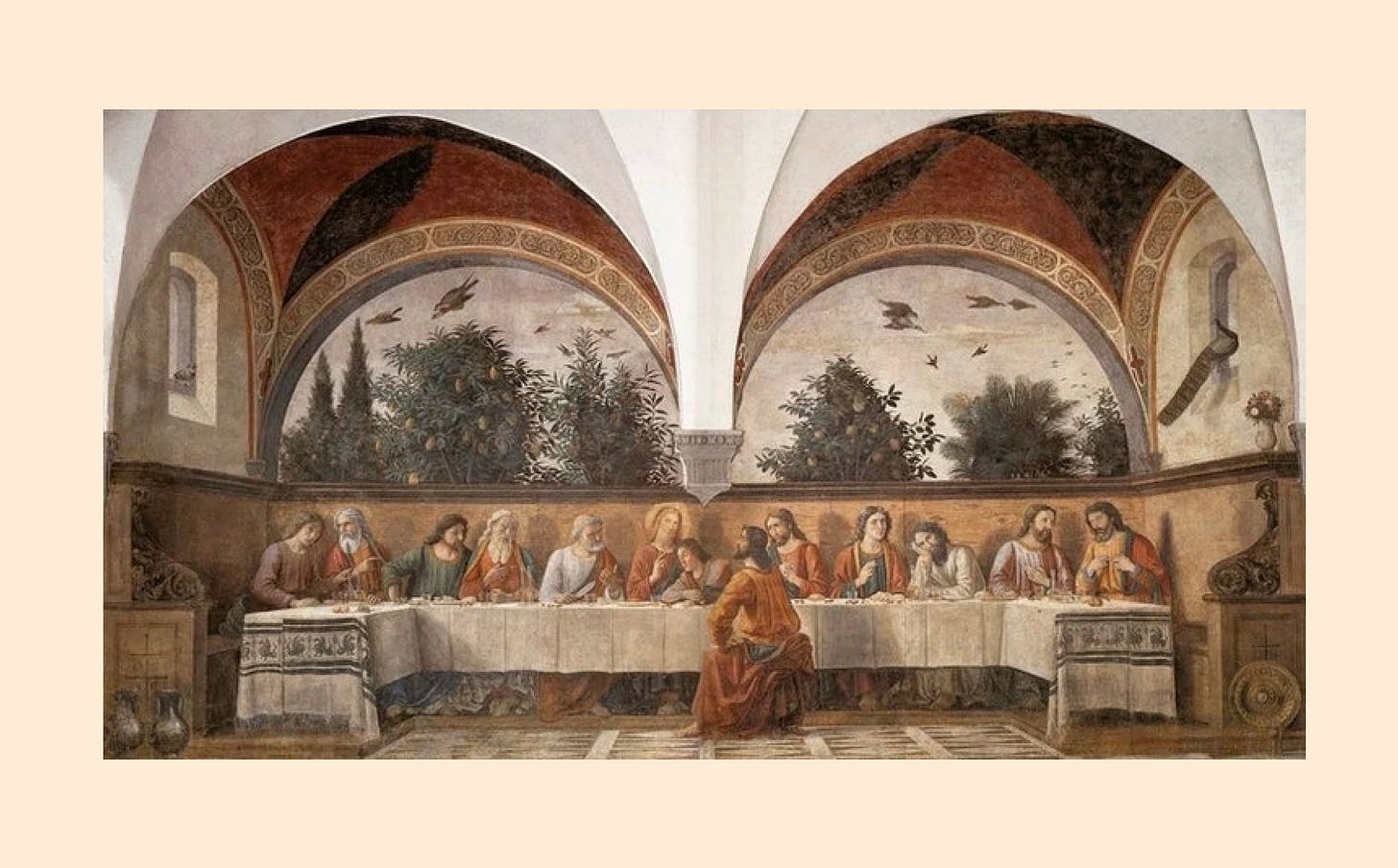

At 528 years old, Leonardo Da Vinci’s painting of Jesus as he announces his betrayal to his disciples is nothing short of miraculous.

But the miracle stems not only from the renowned painter’s technical ability in composition, depiction of perspective, or even the innovations in capturing the psychological anguish in the disciples’ faces. The art, which is now a faint suggestion of its former glory, is still a testament to the genius that made it. Yet the miracle arrives as a simpler fact that after 528 years the fresco has survived two world wars, environmental damage, and restorations, but still stands today at Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan.

There were two journeys that brought us here. The first journey started last year. Fueled by curiosity, I began the effort to rediscover art and uncover the secrets of the old Masters. The second journey begins with obtaining the coveted tickets to visit The Last Supper. Tickets are available only at certain windows and are notorious for quickly selling out. It is critical to obtain them months in advance. Visitors must arrive half an hour early. From there, you must wait patiently for the previous group to exit and then your time slot is called. The painting is a national treasure for the Italian people, but it also represents a kind of artistic inheritance that transcends its religious content because the hands that made it belonged to one of humanity’s greatest individuals, Leonardo Da Vinci.

It was 10:30 am on the 25th of January. It was a bright day, easily overlooked as just any other day. On this day, I turn 31 and fulfill my dream of seeing this masterwork in person. When I entered Santa Maria delle Grazie, I did so nervously. This is not an exaggeration. Witnessing the Last Supper took my breath away. I had exactly 15 minutes to stand in awe before I was ushered out. A painting of this size, like a novel, is meant to be read slowly and carefully. It is unfortunate that here one is not afforded this privilege but it’s also understandable. In order to preserve the fresco, strict environmental guidelines have been put in place. The duration and the amount of people at any given time is tightly enforced.

I’d been looking forward to this moment for 15 years and had only 15 minutes to see it. I had to make them count. A painting must be experienced first and only then is taking a photo appropriate. A photo will only serve as a souvenir of the moment. Any attempt to capture a painting beyond this is pointless. Photos will never do the paintings justice. Quickly, I scanned the fresco absorbing as much as I could. But what is so special about this painting? Were there not already plenty of other paintings of this pivotal moment?

In 1494, at the age of 41, Da Vinci, then living in Milan, was commissioned to paint a fresco for a dining room serving monks. It took him four years to complete. One can only imagine what it must have been like during those first days after its completion. Painting frescos is not easy. There is no room for error and the process is unforgiving and painstaking work. Leonardo was always experimenting. Always innovating and pushing his process. That was his edge. However, when it comes to frescos, this approach would prove to be the unfortunate downfall of his masterwork. Because just after it was made, it soon began to fall apart due to the experimental technique Da Vinci used. It is impossible to overlook how much damage The Last Supper has sustained over the centuries. Someone even had the audacity to add a door splitting the composition near the bottom of the table. Yet, in its frail state, it continues to offer us a glimpse of a glorious artistic past.

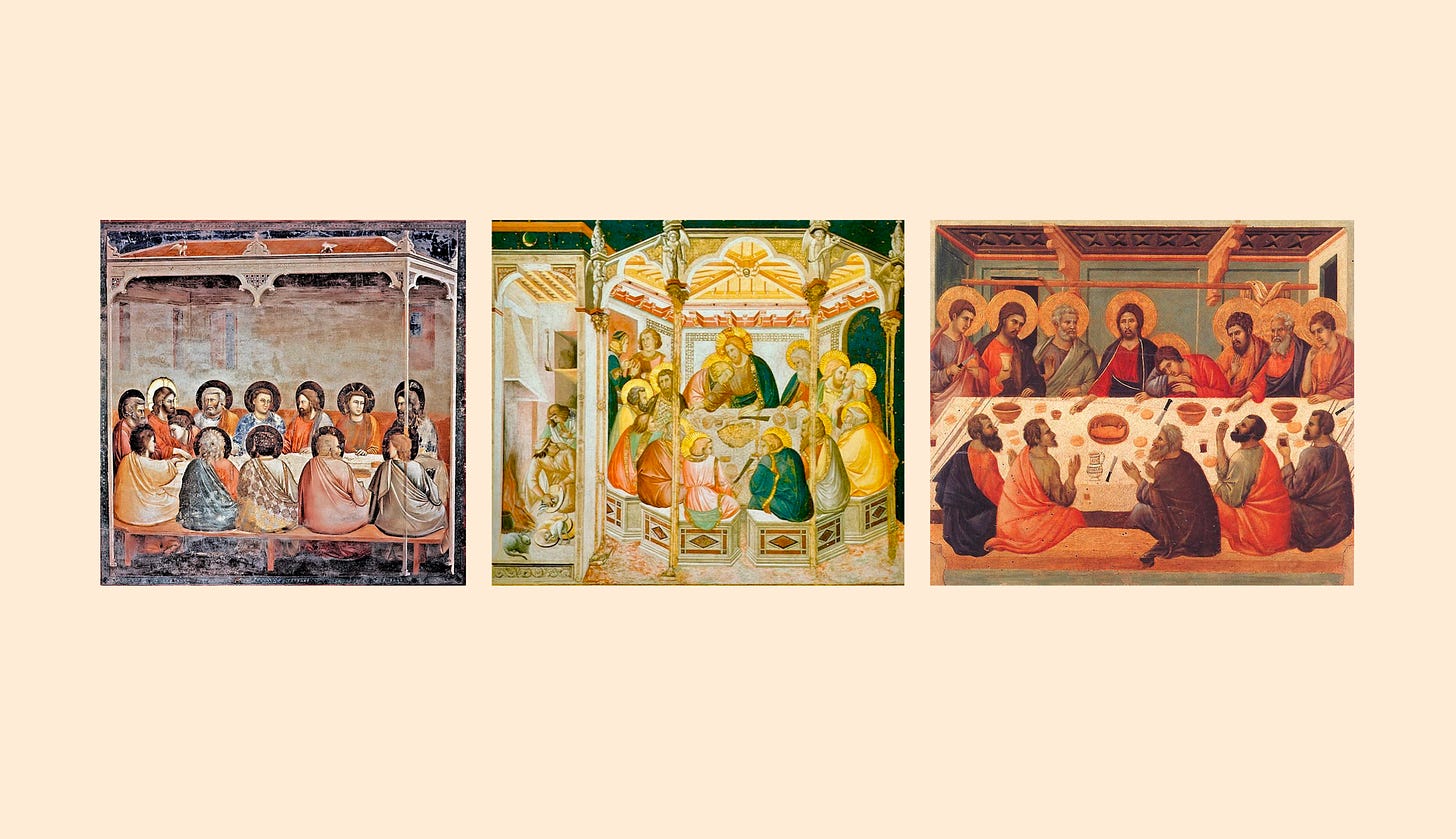

The reason history remembers this version is that Leonardo presented a design unlike any other before. Because of Leonardo’s intense study of facial anatomy, he was able to capture the exact moment of shock that the disciples experienced individually as they hear that one of them will betray their teacher. Notice, that previous interpretations, while beautiful in their own right, feel almost primitive and static when compared to the leap made by Leonardo in his design.

The fragility of the Last Supper is an alarming reminder. We’re witnessing a piece of art slowly fading. I fear we also risk losing the craft of drawing and painting. The Last Supper can serve as a source of inspiration and a call to action. If we don’t learn how to draw and compose, we won’t have the grammar and skillset required to materialize new visions. We could find ourselves in a stagnant and artless world. To be clear, I’m not advocating making art go back to depicting religious scenes. On the contrary, I’m reminding us of what’s at stake and of the beauty discovered in going deeply into our rich artistic inheritance.

We can start building upon this shared inheritance by first recognizing that making art is not easy. It’s not a skill acquired overnight. Even the masters didn’t get it right the first time or called themselves experts. You don’t just learn how to draw and keep the skill forever. You must continuously work to keep it. Additionally, things are not just art because someone with a loud voice declares it so. I’ve been studying and practicing drawing for some time now and I’ve yet to make anything I’d dare call art. I’m honest with myself and my work is just not there—yet.

There is a difficult and tedious journey ahead for those who wish to produce great work. Calling oneself an “artist” is easy so their aim is not rooted in acquiring that title. Their fuel is the ever-present desire to seek so that they may, at least, leave behind evidence of their noble attempt. They are well acquainted with failure, but they lean on their patience. They respect the craft and create with integrity and time. They know the rules and study how to bend them with intelligence. Art with integrity respects tradition and speaks directly to the things that make us human. It exposes our minds to the splendor of a new vision by showing us how far we can go by making a new contribution to its namesake. If what we produce fails to exceed, or at least reach the standard set by those who came before, it should be called something else and not art.

Art with integrity respects tradition and speaks directly to the things that make us human

LuVv it BruVv

As with all your work superb

And on your birthday

Lachs is on me

Seeing The Last Supper in person was one of the most profound experiences I have had with a work of art. Having 15 minutes to look, really look, at a masterpiece without interruption is a rare privilege.