“If heaven would only give me five more years of life I could become a truly great painter.”

Hokusai’s final words at age 88

To become skilled at drawing, one must make peace with a terrific truth: learning to draw well can take a decade or more, and learning to draw great will take a lifetime. The degree to which one achieves excellence depends on the person. But perhaps, you are invested in another profession, so you might ask, what benefit does a deeper knowledge of drawing hold in store for you? We might even reframe the question to be how does understanding drawing help us better understand art?

Art may be consumed without much thought just as any person may enjoy and benefit from a nutritious meal set before them, without a word, at a fine restaurant. Yet to the few whose hunger transcends their biological needs, they may recognize in themselves a desire to learn more and ask their server eagerly “How was this made?” It is to those who wish to see more than fine pictures to whom I now write.

In order to begin the study of drawing, one must abandon the barbaric and prevalent misconception that drawing is made at random and brought to paper by talent alone. In a master drawing, crafted in the classical tradition, nothing is ever random. Every stroke is carefully planned and placed. However, it is until the viewer learns to read the master drawing, that the intellectual and emotional interplay woven into a drawing becomes recognizable. Among the various techniques employed by the master draughtsmen is the use of proportional relationships between shapes to organize the contents of their compositions through lines.

The Shape of Beauty

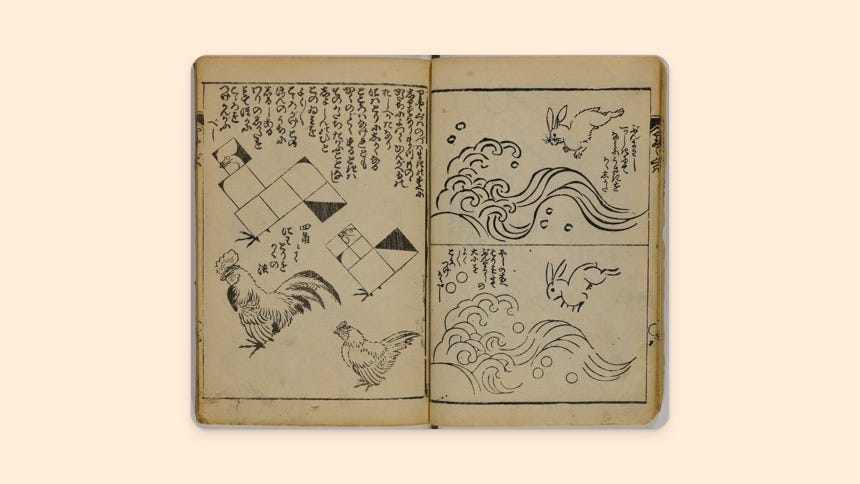

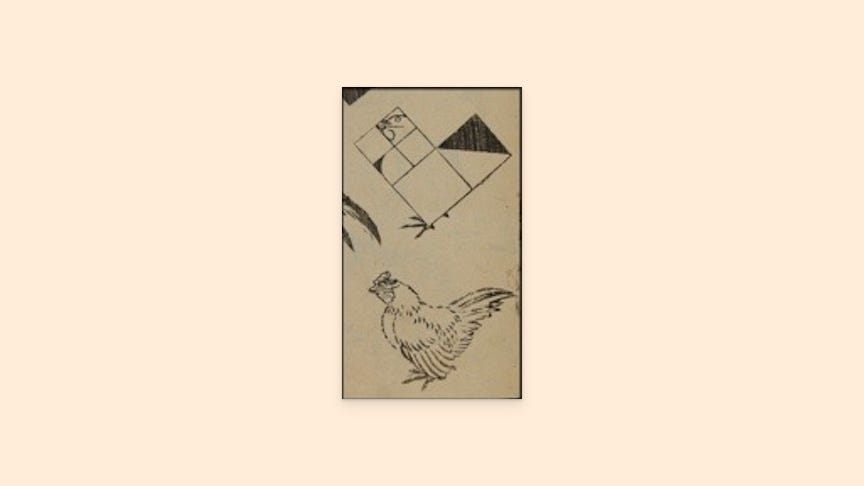

Since we’ve been able to stand vertically and ponder things, patterns (and the relationships that enable them) have fascinated us. And for the advanced, the connection between numbers and beauty became a subject of study and for an even greater few: an obsessive practice. The origin of numbers that govern the relationships of what the viewer sees sprouted from Mother Nature herself. With hopes of gaining more insight into the underlying structures in drawing through the intentional use of proportion, I came across an instructional drawing of an artist who became the subject of this essay.

The instructional drawing pictured above came from Katsushika Hokusai who in these pages shows us so elegantly the proportional relationships between shapes in designs for a rooster and hen. For instance, notice how the set of four little squares that make up the hen’s head design can fit into the hen’s breast, which is one large square.

Who was Katsushika Hokusai?

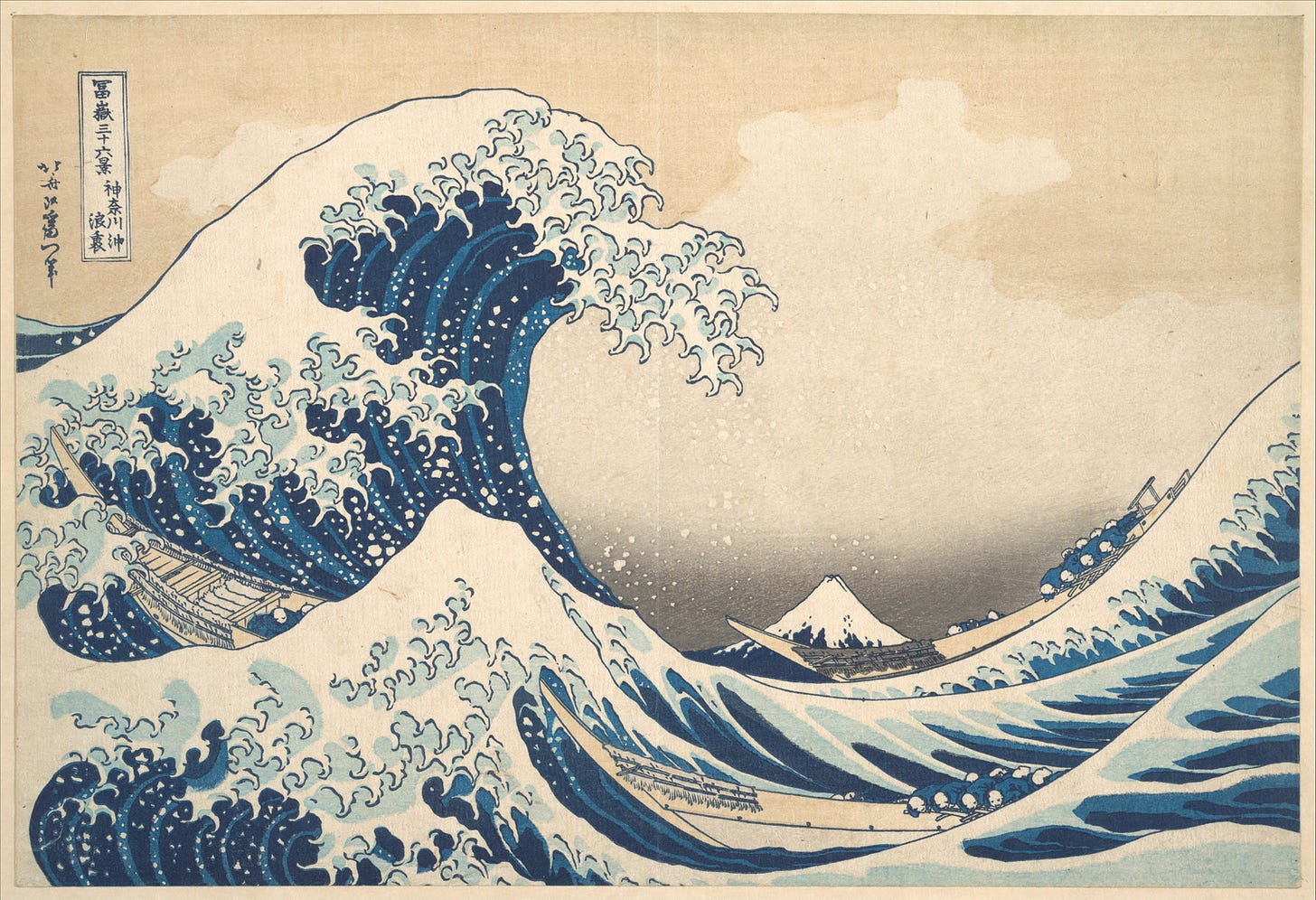

Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) was born in Edo (present-day Tokyo) during the Edo Period. Lasting from 1615 to 1868, the Edo Period was a time of political and cultural stability in Japan, during which the country was closed off from the outside world. The military government, or shogunate, reigned strong control over society and the arts. It is likely you may not recognize his name, but you may be familiar with one of his most notable and iconic landscapes from a remarkable series titled Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, first published between 1830-1835.

Early Years

Hokusai displayed a mania for drawing early in life. He was adopted at the age of four by a mirror designer employed by the Tokugawa royal family. At the age of fourteen, he learned the craft of woodcutting and engraving designs from local painters. Eventually, Hokusai would become one of the greatest masters of ukiyo-e, a genre of woodblock prints and paintings that flourished during the Edo period.

"Living only for the moment, turning our full attention to the pleasures of the moon, the snow, the cherry blossoms, and the maple leaves; singing songs, drinking wine, diverting ourselves in just floating, floating; caring not a whit for the pauperism staring us in the face, refusing to be disheartened, like a gourd floating along the river current; this is what we call the floating world."

-Asai Ryōi

An Emerging Technique

During the Edo Period, the political ruling class were patrons of the arts and they favored the Yamato-e style of painting. The name Yamato-e literally means “Japanese painting” and it is characterized by its use of bright colors, gold leaf, and elaborate compositions often depicting themes of religious and imperial significance.

Needless to say, after hundreds of years of the same thing, the artists started getting bored. A new form of painting, designed for the average person, begins to emerge. That’s when things begin to get more interesting. This new style is called Ukiyo-e meaning “pictures of the floating world.” The subject matter reflected the fleeting world and preoccupations of urban life with a hedonistic bent.

A Colorful Breakthrough

In 1765, when Hokusai was just a toddler, a breakthrough in tech made it possible to produce prints in color. This was big. Color is common to us now but back then, this was a radical transformation. The traditional woodblock, previously restricted to monochrome designs, was now able to provide the artist with a new layer of creative expression.

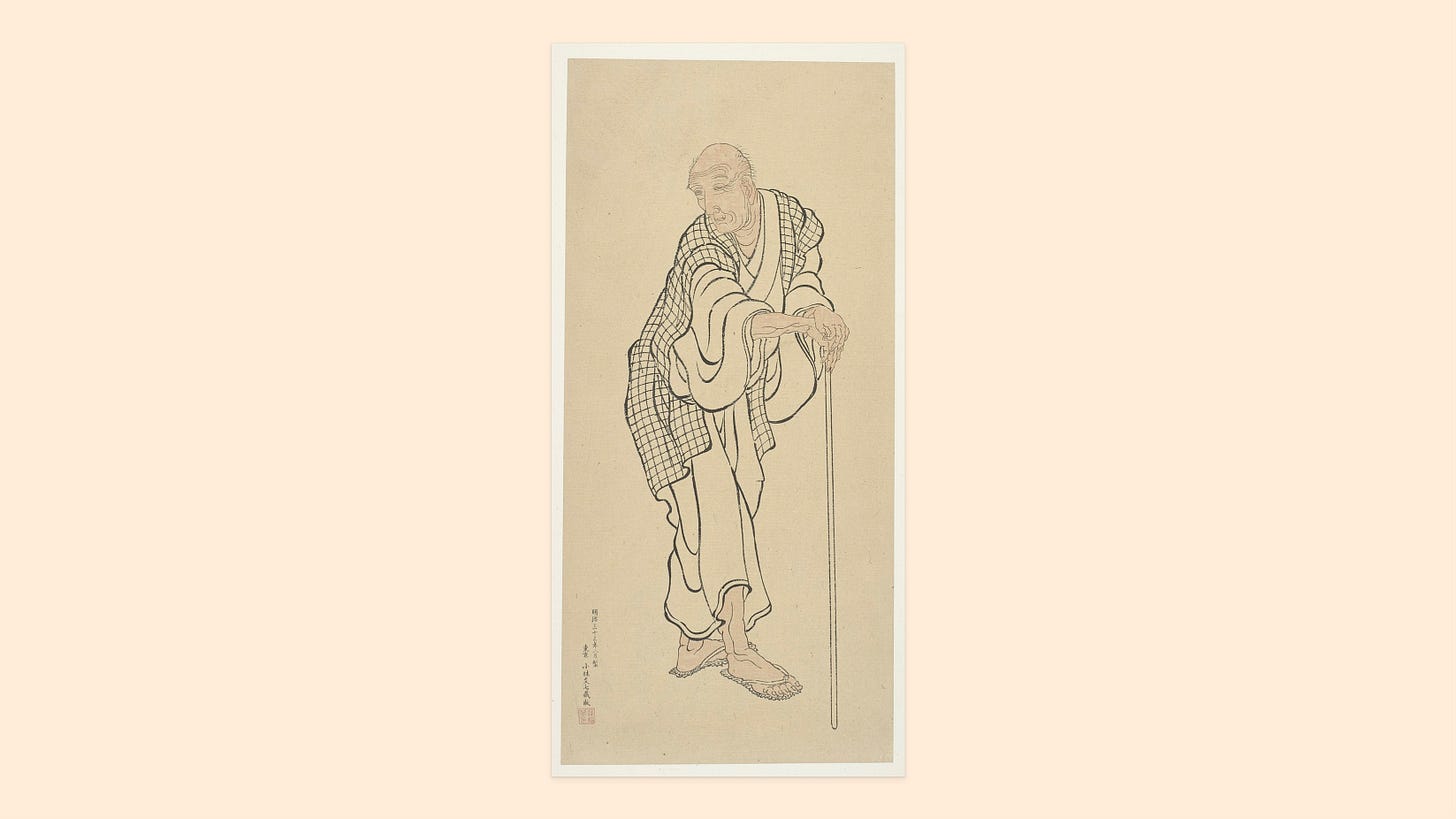

Hokusai, who was known by at least 30 different names during his lifetime, was a master of composition and color. His work is characterized by the dynamic use of line, form, and perspective. As his many names may suggest to the perceptive reader, his work explored different styles and techniques. Hokusai produced numerous instructional drawing guides offering insight into his process. However, we are surrounded by both opportunities and obstacles in our attempt to obtain these lessons.

Over the past week, I’ve been on the hunt for these books. So far, I have only been able to collect scanned pages from four volumes. To my great disappointment, many of these old texts have long been out of print, making owning them quite difficult. The thought of losing this knowledge haunts me. If I can’t find Hokusai’s texts, I plan to create facsimiles for the library. Great treasures are shown in the pages of these books.

A Furious Dedication

Hokusai writes this:

"From the age of six I had a mania for drawing the shapes of things. When I was fifty I had published a universe of designs. But all I have done before the age of seventy is not worth bothering with. At seventy-five I'll have learned something of the pattern of nature, of animals, of plants, of trees, birds, fish and insects. When I am eighty you will see real progress.

At ninety I shall have cut my way deeply into the mystery of life itself. At one hundred, I shall be a marvelous artist. At 110, everything I create; a dot, a line, will jump to life as never before. To all of you who are going to live as long as I do, I promise to keep my word. I am writing this in my old age. I used to call myself Hokusai, but today I sign myself The Old Man Mad About Drawing."

Hokusai was fiercely dedicated to the journey. It is with this spirit that we must seek to embody. And though the pursuit of excellence is often a lonely one, especially when it pertains to the arts, one does not need to look too far in history to find other mad people crazy about something we’re crazy about to find company.

More to uncover

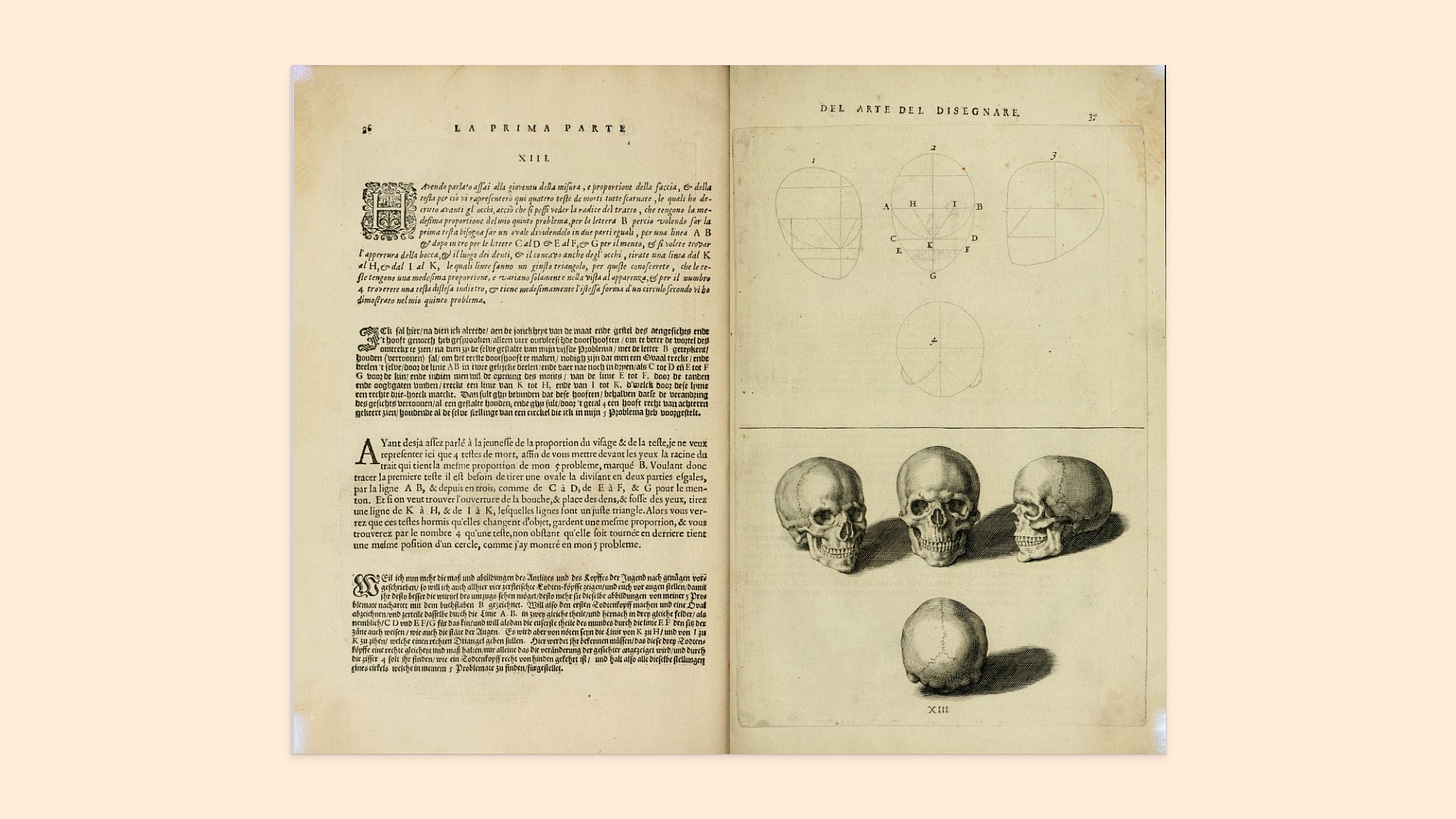

In the process of writing this, I came across another rare book I hadn’t heard of by Crispijn van de Passe (1594-1670) titled The Use of Light in Painting and Coloring published in 1643. Only four copies of this manual appear to exist in the United States. If you read Dutch, French, Italian, or German you are in luck because this exquisite text can be found here.

Coda

If you found this essay valuable, consider supporting Still Life by sharing it with a friend or becoming a paid reader. Your contribution makes it possible to keep this expedition going. Thank you for reading and happy new year!

Fascinating read. Thank you. Reading about the floating world has reminded me pick up the Ishiguro novel again.

Nice read Aaron! Thank you for sharing.